The magical reign of New York’s most eccentric speakeasy salon.

On a steamy August night in 2014, Dan Chung approached an unmarked door in an apartment building on 84th Street on Manhattan’s Upper East Side. According to an article he’d read in the New Yorker a few years earlier, behind the door lay a cozy bookstore filled with chatty authors and presided over by an eccentric, Brooklyn-accented proprietor.

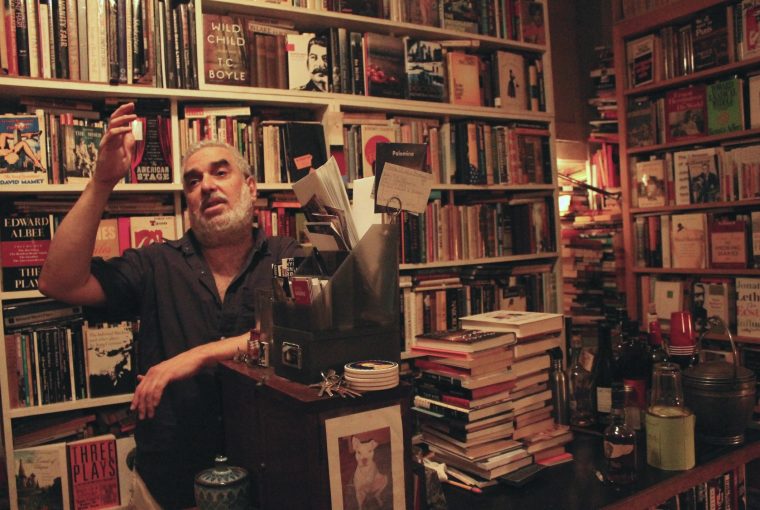

According to lore, Brazenhead Books had once occupied a ground-level storefront in New York, but rent hikes forced owner Michael Seidenberg to pack up his stock and rehouse it a few blocks away inside his rent-controlled apartment. It began filling up so quickly that he had to remove the kitchen appliances, and then move himself and his wife to another apartment nearby.

The first night that Chung visited, there were only a few others sitting among the stacks, drinking and chatting. As he left, Seidenberg invited him back, for a poetry night in honor of the author Charles Bukowski’s birthday.

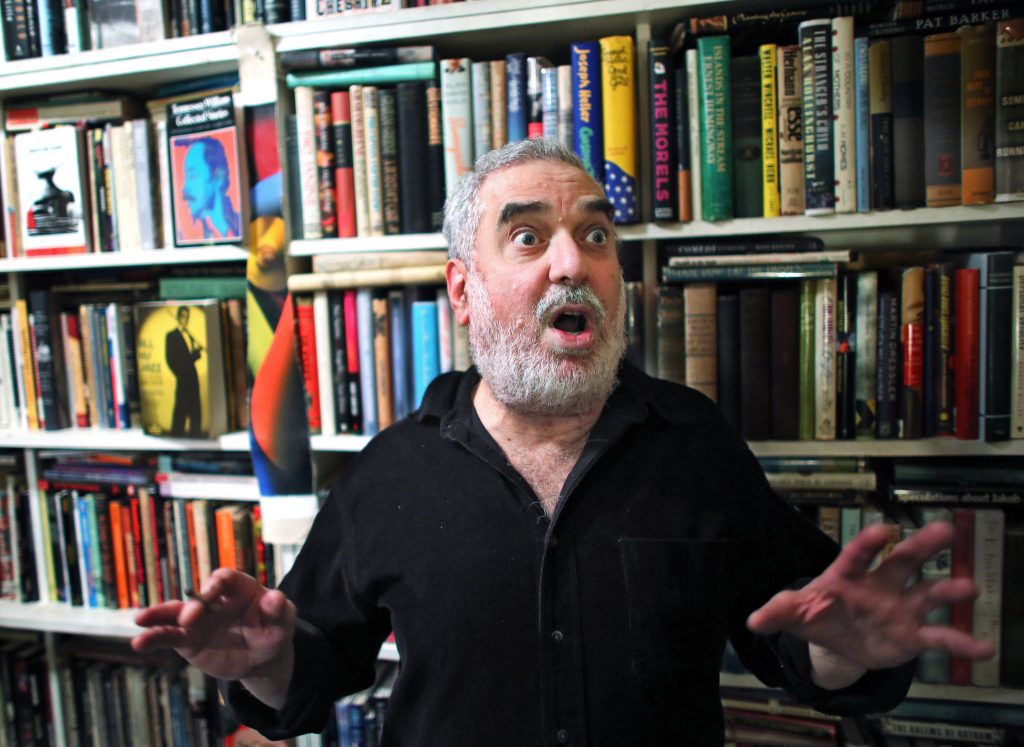

“It was done in the style of Michael,” recalls Chung, “Which was: come as you are, do what feels right to you. If you want to read a poem standing up, read it standing up, if you want to read it sitting down and muttering under your breath, that’s cool too. Everyone there was just very accepting and welcoming.”

Over the years Brazenhead was home to nights of all varieties. On some, 40 or 50 people might be crammed into the space, dripping with sweat as the single air conditioning unit sputtered hopelessly. The books tilted precariously from piles on all surfaces, leaving only small gaps for the windows. A makeshift honor bar sat on a bookshelf of biographies, where Seidenberg could often be found with a tumbler of whiskey in hand, holding court on his favorite authors and topics of the day.

“It’s a bigger thing than a bookstore — it’s a community of writers,” Seidenberg told the New York Times in 2015. “Dylan Thomas is not drinking in the West Village anymore. Kerouac and the beats are not hanging out. So this is a place people can come. You don’t even have to be a book person.”

There was a weekly poetry night on Tuesdays, and Thursday and Saturday were open salons, meaning anyone was welcome to mingle, hold court, or just listen to the conversations. On some nights, editors of the literary magazine The New Inquiry would meet.

Out of an apartment on the Upper East Side, Seidenberg had cultivated a community of misfits, a place his regulars sometimes jokingly called an orphanage. “You could tell a lot of people were tired of the New York culture of bars, nightclubs, readings, and events with Q&As,” says Chung. “Brazenhead was a place where every night was something different: a different group of people. A different feeling. Michael would be in a different mood. So it was constantly changing and that in itself was exciting.”

But when the landlord died and his successor noted the rent controlled tenant who clearly did not live in an apartment with thousands of books but no kitchen, Seidenberg received an eviction notice. By then, in 2015, Brazenhead had survived eight years as an all-night business, bar, and event space run clandestinely out of a residential building. He didn’t fight it.

Without much fanfare, the stock of books moved to Seidenberg’s real residence, a larger apartment just a few blocks south. Books once again reached the ceiling, though in a more linear fashion. Poetry and salon nights resumed, though less regularly, signaled by a bell hanging in the living room. Seidenberg began spending more time at a home he’d purchased in upstate New York, and Brazenhead transitioned into a calmer space for small gatherings.

“Brazenhead was a bookstore that was more than a bookstore because everyone was welcome to come there and do whatever they wanted,” says Gracie Bialecki, who worked as Seidenberg’s assistant. “There were no expectations. There was no pressure to spend money, to be somebody, to impress anybody. There was no time limit. That that spirit of freedom is pretty hard to find in New York, unfortunately.”

Bialecki had arrived at Brazenhead one night as the late-night afterparty to a book reading in Brooklyn. As she left that first visit, she cried in the hallway outside Seidenberg’s door. “I was worried I would never be able to come back because it just didn’t seem possible that it could actually exist,” she says. But she continued to return, eventually helping the man she calls “the Buddha book God of New York City” move thousands of books into his new space.

In 2019, at age 64, Seidenberg unexpectedly passed away from heart failure. The final salon held at Brazenhead was his memorial service. As they had for more than a decade, dozens of artists, filmmakers and literary types squeezed among the bookshelves to toast the proprietor from 3 p.m. to 3 a.m. on a warm July day. “I think I might be Patient Zero,” said author Jonathan Lethem, who started working for Seidenberg in the 1970s, in a speech. “You all self-selected to be part of this tribe.”

Seidenberg once told Bialecki that the reason he never went anywhere was because he was so fulfilled in the space he had created. He could sit still. “He just had that attitude and energy,” she recalls. “He could be unconditionally welcoming. He could be genuinely happy. He was excited to see you. He was happy to get a call at 1:30 a.m. And you could tell he was somebody who had figured out how he wanted to live his life and was living it that way.”