While the era of Germany’s Weimar Republic is largely remembered for its extreme decadence and as a precursor to the Nazi takeover, it was also an era marked by women, transgendered and homosexual people entering the workforce in a highly visible way, and wielding political influence. Women were given the right not only to vote in 1919 by the Weimar Constitution, but also the right to hold office. So many men had died or become physically and psychologically wounded in World War I, the electorate became increasingly female between 1919 and 1933, ultimately becoming the elected majority. This marked the rise of the ‘new woman’ between World War I and World War II.

Psychologist Alice Rühle-Gerstel identified as one of these so-called ‘new women’ in the 1920s. She observed, “Women began to cut an entirely new figure. A new economic figure who went out into public economic life as an independent worker or wage-earner entering the free market that had up until then been free only for men. A new political figure who appeared in the parties and parliaments, at demonstrations and gatherings.” Salon culture had a massive influence on women’s liberation in Germany, because while salons had become a traditional social institution in Paris by the mid-18th century amongst the aristocrats and bourgeois alike, these early Berlin salons rejected pretension and anything that glorified “high society.” They were much more bourgeois in their emphasis on simplicity, authentic expression of feelings, amusement and mutual education.

Spearheaded by affluent Jewish women, who enjoyed a protected status of socio-economic privilege by virtue of their families’ financial contributions to the German crown, the first salons of this era were hosted by the Itzig daughters, Sara Levy in Berlin and Fanny von Arnstein in Vienna. Since most Jewish communities were quite insulated from the rest of society and operated by their own rules and customs between the 18th and 20th centuries, Jewish women typically received an education. Not only were they able to create more social and political mobility for themselves and women generally in the 20th century, their protected status was effectively shared with the then very underground LGBTQ+ community of Berlin.

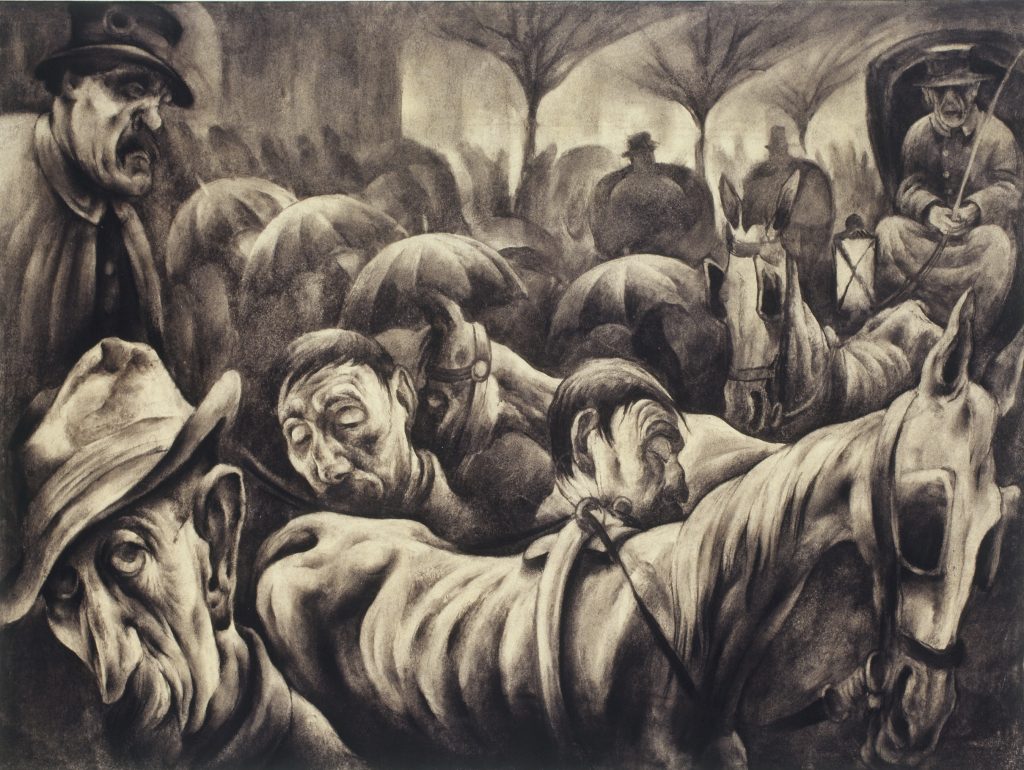

Along with the so-called new woman came a new worldview promoted through the art of the day, neue sachlichkeit, which translates to ‘new objectivity.’ The lens of modern art through which the Weimar Republic began seeing itself included hyper realism capturing the day to day lives of Berlin prostitutes, injured, downtrodden war vets and flagrant drug use, while celebrating women, homosexuals and trans people. The new German woman became an icon of modernity during this period between World War I and II, and all the most important matters of the day were discussed in the homes of these increasingly influential women. From the perspective of neue sachlichkeit, conservative Christian values had no relevance and practicality was the new moral authority. Having a segregated society where certain people and interests were marginalized, was simply impractical.

While in early 20th century Paris Jewish-American expats Gertrude Stein and Natalie Clifford Barney were hosting salons with the artists, writers and intellectuals that were directly influencing art and politics on a global scale, in Weimar the cultural and socio-political influence women was obtaining much more immediate. But their rise was short-lived and sadly set the stage for the Third Reich fascism. War veterans began returning to civilian life, reclaiming their roles at work and in the family, while politicians began to advocate that women return to the more traditional roles of wife and mother. Germany began promoting Mother’s Day as a national holiday and with it the slogan Kinder, Küche, Kirche (“children, kitchen, church”) as the proper place for women.

When the Nazis took power in Germany in 1933, the Weimar Republic fell and with it, all the civil liberties its culture had fostered over time. Learn more about the influence of salons at the turn of the 20th century in Paris in our expose on salon history and check out the immersive art installations Berlin’s iconic Berghain nightclub hosted during Covid.