Salons are nothing new, humans have been gathering together to discuss and debate ideas, and to share and savor new literature and music for centuries. They fall in and out of trend depending on the era, but for a solid 400 years or so, from about 1500 – 1900, salons were popular across Europe. The term salon suggests some modicum of regularity, say, weekly, (alright, that’s too much! Monthly ok!) and with that regularity came conversation, connection and community. Sometimes salons centered around a specific theme like poetry and at other times they were more general in scope. But the one central theme amongst them all was that the focus was on listening and speaking to each other, learning from those around you, your fellow guests at the salon.

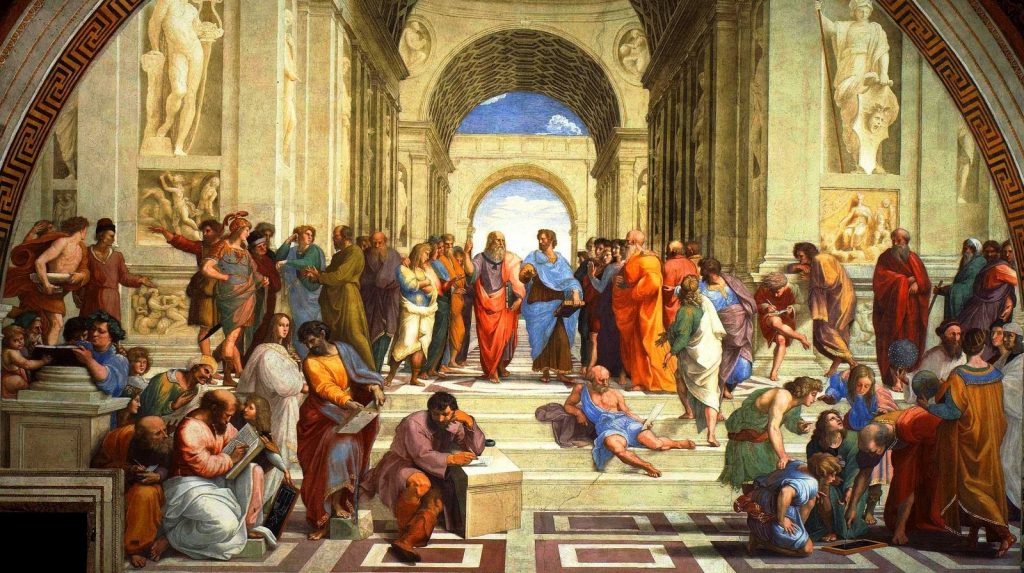

While the roots of the salon can be found in Ancient Greece and Rome, the first recorded salons took place in Italy in the 15th Century, and these were a precursor to the Enlightenment Period. They were an opportunity for artists, poets, musicians, thinkers, the Renaissance intellectual glitteratti and their hangers-on, to come together across social classes to hob-nob and share ideas out of the scrutiny of the Roman Catholic Church.

Noble women hosted these Italian salons and even then, the host was seen as inspired, bright and a trend-setter. Isabella d’Este (1474-1533) and Elisabetta Gonzaga (1471 – 1526) were sister-in-laws in Renaissance Italy who hosted salons that had a huge reach. The two of them wrote letters back and forth to each other often so the intricacies of their lives are well-documented. Their salons were written about by Baldassare Castiglionein in The Book of the Courtier, which set the standards for how one was to behave, speak and dress at these Italian Renaissance salons. They are credited with having had such an influence with their gatherings that France picked up on the trend and thus, the world of French salons was born.

Once neighboring France picked up on the trend, they ran with it all the way back to the Rue St. Honore in Paris. If you’ve heard of salons before, what likely comes to mind are the French salons of the 17th and 18th Centuries where philosophers, authors, musicians, poets and other interesting and educated people with points of view came together to talk and share ideas about science, politics, literature and art. (Salons were happening across Europe but were particularly popular and influential in France). So analog!

Like in Italy, these salons were hosted by prominent, educated women in their private homes. The female hosts (later the term salonniere became used) did all the inviting and curated the evening of conversation, art and music. It was a rare chance for a woman to be both in control and have some freedom of expression in the male-dominated world and to be at the epicenter of the exchange of important ideas.

Women were not allowed formal education during this time, so the salons also provided an acceptable way to educate oneself. Woe-betide you if you got on the wrong side of the salon host; you would not be invited back. And you couldn’t just walk up to a salon evening at someone’s home and attend as a guest, absolutely not. You needed a letter of introduction. That’s not so different from now of course, if you were having a dinner party that looked all twinkly and inviting from the sidewalk, you wouldn’t just let anyone in off the street to attend. Obviously not!

One of the most infamous early salon hosts in France was Catherine de Vivonne, the Marquess de Rambouillet. Hailing originally from Italy, she found the French Court not to her taste. She set up her home called the Hotel de Rambouillet as a place for the educated to gather upon invitation, and made it warm and welcoming for people to come over and speak intimately and openly. Everyone who was anyone with an original thought during that came through Catherine’s home during the mid-1600’s. Now that’s quite the salon host!

The most well-known French salonista pioneer to immediately follow in her footsteps was Madeleine de Scudéry. Known for creating her own ideal of a feminist utopia within her salon, she strictly forbade romantic and sexual love, as she herself was devoutly celibate. Emulating the format perfected by Marquess de Rambouillet, de Scudéry declared her salon to be its own sovereign country within her heart, and even created a map of how to achieve that status of her affections called La Carte de Tendre (Tender Card). Her era of hosting still reflected a time when an invitation to her salon was a rite of passage into Parisian aristocracy. So to successfully reach the most tender part of her heart by way of La Carte de Tendre, in a way became its own form of social nobility.

What was extraordinary about the earlier 18th Century salons in France is that they brought people from different economic classes together (unlike, say, the court at Versailles which was just the very fanciest people, the nobility) and let them exchange ideas openly in a safe setting. In a private home in a pleasing room you didn’t have to worry someone was going to chop your head off later that night because they disagreed with you, radical! Certainly we could learn from that today, and this is what makes salons so very timely and valuable both in this age as well as hundreds of years ago.

This period during the 1700s into early 1800s was called the Enlightenment, and it was a time when free-thinking flourished. That is, having your own point of view – to be listening and learning and debating ideas, was celebrated during this time. It was not cool to be dumbing oneself down amongst the fashionable and bright salon-going crowd, and the French believed that an educated and enlightened society was for the good of all.

With the French Revolution came Napoleon marching in and salons took a bit of a turn under his rule, becoming less radical and more formal. Perhaps they were less interesting intellectually too, as Napoleon did not want to encourage too much free-thinking amongst his people, and firmly believed the powerful position women occupied as hostesses was fundamentally dangerous. He banished one particularly controversial salonista, Germaine de Staël, who was not allowed to come ‘within 40 leagues of Paris’ for ten years beginning in 1803. According to the Memoirs of Madame de Rémusat, another member of the French royal family, Napoleon said she “teaches people to think who had never thought before, or who had forgotten how to think.”

Salons sort of fizzled out in France in the first half of the 1800’s and then returned later in the century with a focus on modern art exhibitions and literature, paving the way for a new era of art-focused salons in the 20th century. Paris continued to be the pulse of the world’s most influential salons, a legacy most famously carried on by wealthy American ex-patriots and authors Natalie Clifford Barney and Gertrude Stein.

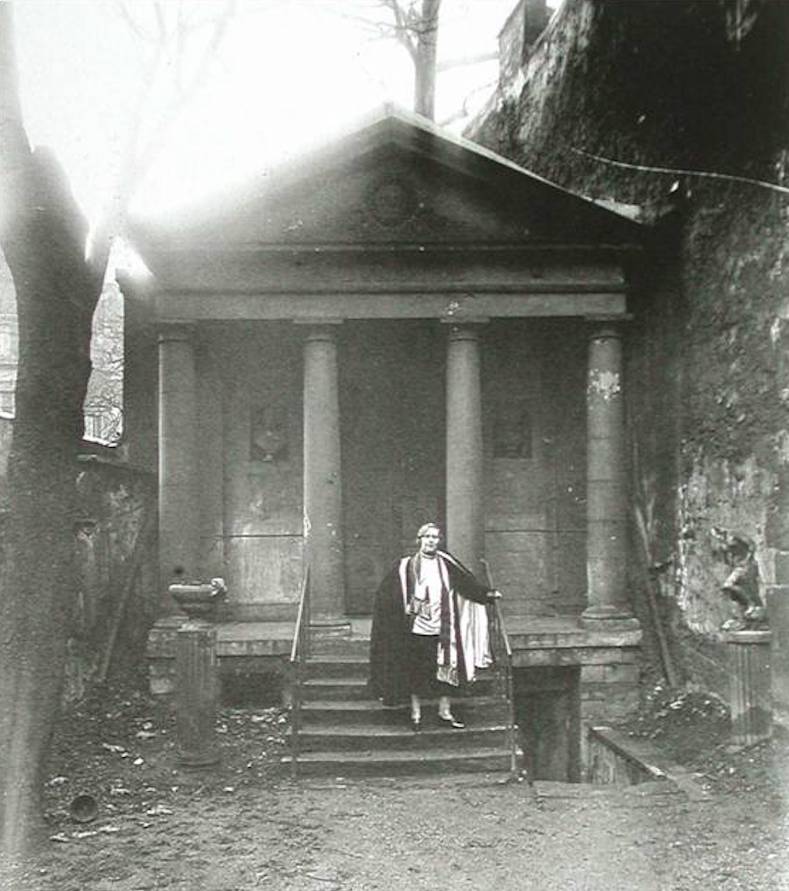

The two shared a great deal of overlap in both their personal lives and salon guestlists, and eventually became friends. Both were open lesbians of Jewish descent who became iconic feminist authors, and both hosted the likes of Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ezra Pound and many more in their weekly salons. Natalie’s place in Paris had an old Masonic temple tucked into the garden, which she deemed The Temple of Friendship. Her salon ran for 60 years, with a a few years of hiatus during World War II because Natalie had to flee to Italy in order to escape Nazi occupation. She returned to Paris in 1949 and resumed her Friday night salon.

Gertrude Stein’s brother Leo, with whom she lived in Paris, became an early patron of Picasso and other highly influential modern artists, naturally bringing them to her weekly salons. Early collectors of Matisse, Cezanne and Renoir paintings, Gertrude’s salons in the Stein home became an equally powerful a magnet for the most brilliant minds in literature. From 1910 on Gertrude lived with her life-partner, fellow American and writer Alice B. Tolkas, about whom she would later write The Autobiography of Alice B. Tolkas. Deemed the ‘Mother of Modernism,’ the creators who passed through Gertrude’s salons defined the modernist movement in both literature and art in the early part of the 20th century.

Gertrude and Alice bravely stayed in Paris even after German occupation began. World War II devastated much of Europe and with it most of the salons of the day. Their hey-day ran parallel with the salons of the Weimar Republic as well as A’lelia Walker’s famous salons of the Harlem Renaissance from 1915-1930, which attracted iconic writers like Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston. A’lelia Walker helped launch a multi-million dollar direct-to-consumer beauty products company with her and became the premiere arts patron, philanthropist and salonista of her time.

And she wasn’t the only woman hosting salons in Harlem back then either, author Zora Neale Hurston, Ruth Logan Roberts and Georgia Douglas Johnson were also bringing together leading figures of the day in African-American politics, art and literature. These salons arguably propelled the revival of African American culture referred to as the Harlem Renaissance.

Salons popped up again in Hollywood and New York City in the mid-20th century, but many became rightly or wrongly associated with Communism and were disbanded amidst the Red Scare under the scrutiny of the House Un-American Activities Committee. Most notably Salka Viertel’s salon of World War II exiles-turned-showbiz-folks (patroned by Charlie Chaplin, Greta Garbo and Albert Einstein!) in Santa Monica became the subject of FBI interest and disbanded in the mid-1950s.

Suffice to say the social alchemy of salons have a long and fascinating history of ushering in paradigm-shifting ideas born of more broad perspectives, and as a result often ruffling the feathers of established socio-political power structures. Doesn’t the time feel ripe to create more where that came from? Let’s shake things up and offer a welcoming forum for community amidst these strange, divisive times.