On Sunday afternoons in the 1930s and ‘40s, an eclectic crowd would gather in the Santa Monica living room of Hollywood screenwriter Salka Viertel. In German or accented English, they listened to music, smoked cigars, and discussed their new lives in exile. There was one thing they had in common: all had fled the rise of facism as it overtook Europe.

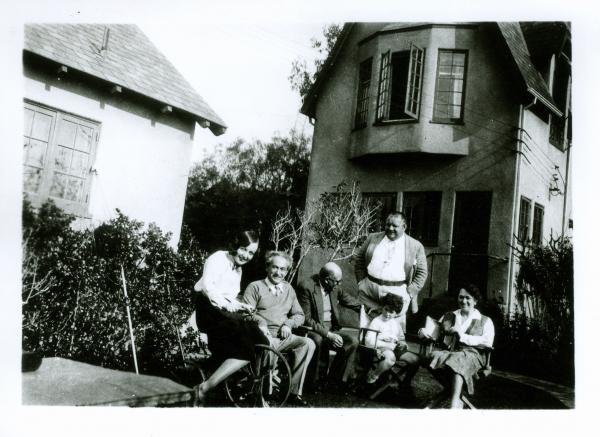

The guest list included the likes of Thomas Mann, Albert Einstein, Charlie Chaplin, Greta Barbo, Aldous Huxley, Marlene Dietrich, and legions of other artists and actors who had escaped the Nazis. They would bask in their shared native tongue, exchange ideas, draft statements about a free Germany, and write letters of support to other exiled groups of countrymen, all with a view of the Pacific Ocean.

Their host, Salka Viertel, was a former screenwriter who had escaped Europe in the late 1920s, and set herself up in Hollywood as a screenwriter. As the Nazi party came to power, she helped new arrivals fleeing Germany feel welcome in California. From her home, Salka created a network of aid that helped her fellow cultural emigres find work, housing, and sometimes even rescue from Germany. Many were family and friends, but she also offered money and assistance to complete strangers. On Sundays, she counseled her guests on how to bridge the divide between brash, fast-moving Hollywood and the more polite, European way of doing business they were used to.

Those who made it to Hollywood joined her German colony, later dubbed “Weimar on the Pacific” by biographer Ehrhard Bahr. Just a block from the beach, their large English-style home sat consumed by honeysuckle and roses. The gatherings “were life-rafts in the form of a few cherished hours speaking in a native tongue, commiserating with friends and compatriots,” Bahr wrote.

Viertel was born into a well-to-do family in what was then Poland Galicia. Her parents kept a French chef on staff at their estate, and though they were Jewish, celebrated Christmas. Determined to have a career in theater, Viertel joined a roving company and traveled Europe. When she returned, her family’s estate was filled with soldiers fighting in the first World War. By the mid 1920s, she had married director Berthold Viertel, and the pair soon decamped to America.

The connections forged at Viertel’s salon changed Hollywood: a chance conversation between a director and composer resulted in the score for The Bride of Frankenstein. Playwright Bertolt Brecht and actor Charles Laughton met there and later staged a buzzy Hollywood play called Galileo. Starlet Greta Garbo, for whom Viertel wrote at least five movies, met her lover Mercedes de Acosta at one party. Brothers Heinrich and Thomas Mann often made long speeches extolling each other’s work. Love affairs, feuds, and life-long collaborations were found in Viertel’s living room.

In The Sun and Her Stars, the first English-language biography of Viertel, author Donna Rifkind describes the host as: “a destroyer of walls, a builder of bridges, a welcome among strangers.” And the group she had collected was “Hitler’s gift to America . . . prodigious individuals who enriched the film culture and the intellectual life of our nation, and whose influence continues to resonate.”

Many of the authors had mocked and parodied Hitler and the Nazi party in novels before they had to leave Europe, but now they continued to do so from afar, some entering a dark, terrifying realm of subject matter as the situation in Germany devolved. But when the war ended, newfound scrutiny was directed at the works of Viertel’s guests and on Viertel herself.

The anti-communist sentiment that tore through Hollywood in the 1950s put an end to their Sunday salons. Viertel’s name was put on an FBI watchlist, she was refused a new U.S. passport, and could no longer get work in screenwriting. The same fate awaited many of her guests, who fled back to Europe and to post-war Germany in the coming years. Viertel was forced to sell her home on 165 Mabery Road and she lived the rest of her life in Switzerland, where she’d still occasionally get a visit from her old Hollywood friends.