When the Soviet model of communal living morphed into tiny, yet private, apartments, there was one room Russian citizens hadn’t had to themselves in years: the kitchen.

Under decades of Soviet rule, millions of Russians who left their villages and came to the cities to partake in industrialization were jammed into shared apartments. Each person was allotted a total of 100 square feet of space and the kitchen and bathroom were used by seven or more families. Rather than fostering a sense of community, these communal kitchens bred fear and resentment. Roommates eavesdropped on each other for hints of anti-Party sentiment, and food supplies were secured in individual rooms or padlocked cabinets. Most families ate in their own quarters.

Then, in 1953, Nikita Khrushchev came to power. In public speeches, Khrushchev pledged reform: he promised the Russian housewife more kitchen appliances, and declared that public food would taste better. Most crucially, he announced that each Russian family would be able to get their own private home.

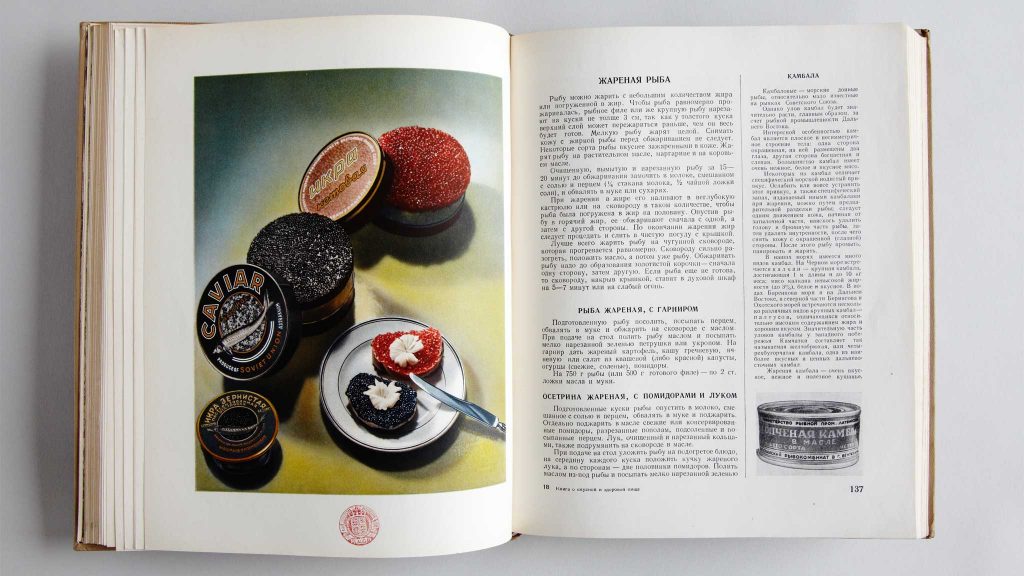

Large apartment buildings began to sprout up across the country with units for individual families. Though they were tiny—between 300 to 500 square feet—Russians celebrated liberation from communal quarters. Finally, they could gather their own kitchens. And as they cooked—from the government-issued Book of Tasty and Healthy Food (although many of the recipes called for impossible-to-get ingredients)—they talked.

Russians had long united politically over food: Bread riots were among the early uprisings of the Bolshevik Revolution, which overthrew Tsarist rule in 1917. When, four years later, rations were cut, Russians went on strike. But after the Soviet Union formed, there would be no more public dissent.

Vladimir Lenin was convinced that citizens were unable to get proper nutrition at home. In the 1920s, he published a pamphlet called Down with the Private Kitchen, deeming in-house cooking as bourgeois, and began peppering the country with government-run canteens. One reason for this, according to the new government, was to liberate women from cooking and allow them to pursue more cultured hobbies. “No kitchen slavery!” shouted one propaganda poster, showing a woman in red pushing open a door to reveal the possibilities outside.

The state-sanctioned meals cost no more than home cooking, yet citizens quickly realized they were another form of rationing and control. It was, as author and Soviet food historian Anya von Bremzen described, a “food dictatorship.” The quality, too, left much to be desired. Recipes were regulated so strictly that each serving of soup was supposed to include the same grams of meat in every canteen across the country—though that number changed depending on if the meals were going into the stomachs of students or government officials.

The years of public dissent were long gone and it was not safe for civilians to voice their concerns—especially in the kitchen. “Communal kitchen was a war zone,” Alexander Genis, a Russian journalist, told NPR. “During the Stalin era it was the most dangerous place to be — in the kitchen.”

Then, after 30 years, the private kitchen was reintroduced. In those cramped quarters, any topic was up for discussion. Groups of friends would gather to debate and commiserate about life under Soviet rule. The intellectual class, long seen as suspect by the state, felt safe voicing opinions in so-called “kitchen circles,” where their tastes and knowledge were valued.

“Kitchens became debating societies,” Gregory Freidin, a professor of Slavic languages and literature at Stanford University, told the podcast Kitchen Sisters. “Even to this day, political windbaggery is referred to as ‘kitchen table talk.'”

The kitchen also became a place to share music, ideas, and literature from the outside world—without fear of nosy neighbors. “Dissident kitchens” took the place of a public forum, which no longer freely existed in the highly censored Soviet Union. Sometimes the poems and writings shared in those kitchens were re-typed, carbon copied, and passed along—a form of underground communication termed “samizdat.”

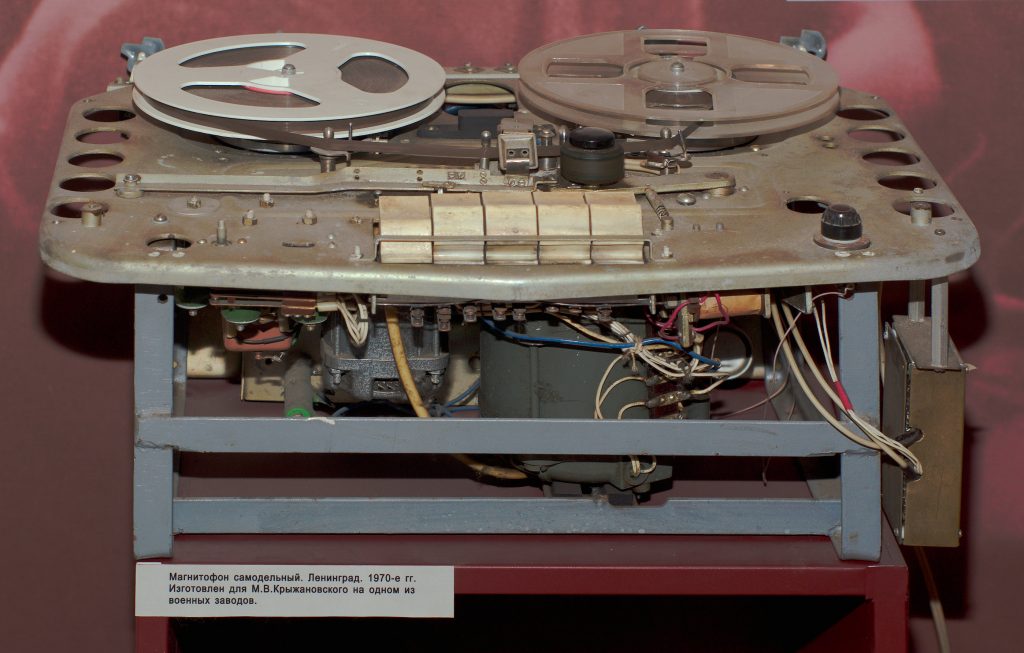

The same went for audio. Magnitizdat, recordings made on reel-to-reel tape recorders, were used to duplicate banned music, or even the performances taking place around the table. One composer wrote a series of songs called “Moscow Kitchens,” in which agitators gather to plan a protest, which later leads to their exile from the Soviet Union.

In one verse he sang: “A tea house, a pie house, a pancake house, a study, a gambling dive, a living room, a parlor, a ballroom. A salon for a passing-by drunkard, a home for a visiting bard to crash for a night. This is a Moscow kitchen, ten square meters housing 100 guests.”

When the Soviet Union collapsed, so did the kitchen circles. Russia’s intelligentsia no longer needed to hide their views, and the shared economic hardships that unified most of the Russian population disappeared with capitalism and fresh class hierarchies.

Yet, memory of the Soviet days hasn’t vanished entirely. Thousands of city dwellers still live in communal apartments and, recently, modern versions of Soviet canteens have made a comeback. Generations too young to remember the hardships of the Soviet Union sit under walls papered with old issues of Pravda, the official Communist Party newspaper, fill up on affordable meals of borscht and pickled herring, and talk.