Jam-packed into a smokey, lavish townhouse on 136th in the heart of New York City’s Harlem neighborhood, arts patron A’Lelia Walker, the only child of America’s first self-made female millionaire, hosted salons attended by the writers, poets, artists, musicians and activists who defined the Harlem Renaissance. Beginning in 1913 all the way through the roaring ’20s, Walker’s home served as a safe space for conversations amongst the most influential African American creators of the day. She eventually dubbed that brownstone the Dark Tower, named after a poem by one of her regular salon patrons, Countee Cullen (“From the Dark Tower”).

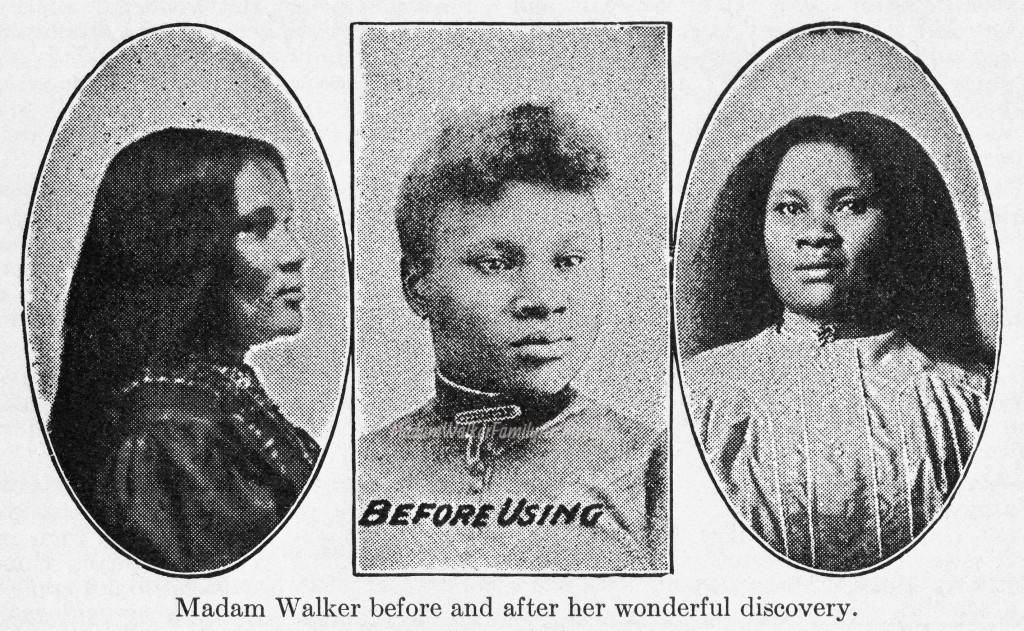

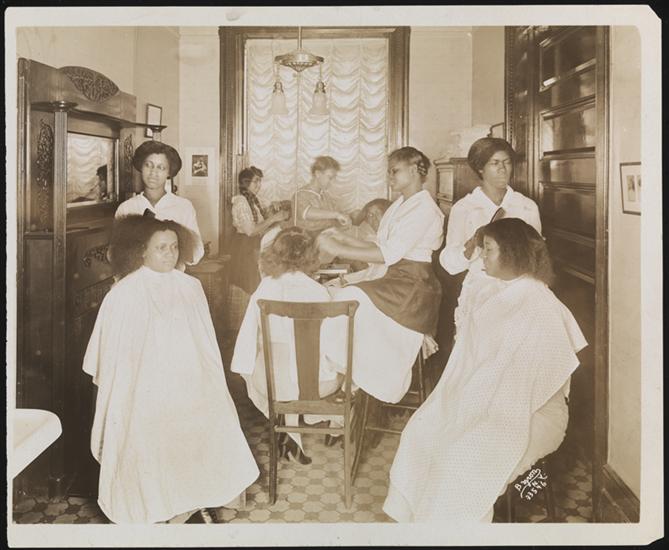

Born Lelia McWilliams in Mississippi in 1885, her mother, Madam C. J. Walker, who was born Sarah Breedlove to former slaves, started a beauty company with her daughter Leila’s help manufacturing and distributing cosmetics and hair care products for black women. In a matter of just a few years, they grew the company into a multi-million dollar empire, thanks largely to A’Lelia setting up a mail-order fulfillment department that eventually grew into a full-blown multi-level marketing initiative with thousands of sales reps. In 1913 she convinced her mother to expand to New York City, which was when they purchased the soon-to-be-iconic townhouse at 108 West 136th Street.

Two years later they purchased the adjacent townhouse and hired one of the first practicing African-American architects, Vertner Woodson Tandy, to turn the two units into a single home, which they called Walker Studios before it was renamed The Dark Tower. The result with a lavish, immaculately decorated, multi-story home that welcomed the likes of Langston Hughes, W.E.B. Du Bois, Muriel Draper, Zora Neale Hurston, Taylor Gordon, Alberta Hunter, Nora Holt, Witter Bynner (aka Emanuel Morgan), Andy Razaf, James Weldon Johnson, and Clarence Darrow. Hughes fondly referred to Walker as “the joy goddess of Harlem’s 1920s,” writing of her in his 1940 autobiography The Big Sea:

“A’Lelia Walker had an apartment that held perhaps a hundred people. She would usually issue several hundred invitations to each party. Unless you went early there was no possible way of getting in. Her parties were as crowded as the New York subway at the rush hour—entrance, lobby, steps, hallway, and apartment a milling crush of guests, with everybody seeming to enjoy the crowding.”

– Langston Hughes

And she wasn’t the only woman hosting salons back then, author Zora Neale Hurston, Ruth Logan Roberts and Georgia Douglas Johnson were also bringing together leading figures in African-American politics, art and literature. These salons arguably propelled what’s since become known as the Harlem Renaissance, a revival of African American culture which culminated in New York’s Harlem neighborhood throughout the 1920s up until the beginning of the Great Depression. But none were as influential or had such a diverse mix of attendees as Walker’s salons, which also became a safe haven for Harlem’s then extremely underground LGBTQ+ community. As historian George Chauncey wrote about that era, “Gay social networks played a key role in fostering the Renaissance, including the extravagant ‘mixed’ parties thrown by the millionaire heiress A’Lelia Walker.”

After her mother passed away in 1919 A’Lelia assumed control of the company and the estate she’d been constructing with Vertner Tandy and her mother since 1916, Villa Lewaro. The 34-room mansion was named by one of their many guests, opera singer Enrico Caruso, who took the first two letters of each word in Lelia Walker Robinson, A’lelia’s real name to make Lewaro. Her salons continued both in her city and country homes, thriving until the onset of The Great Depression, which forced her to sell her beloved Dark Tower home in 1930.

Villa Lewaro was in the press this year when fashion designer Kerby Jean-Raymond hosted a runway show at the estate to reveal his first collection, Pyer Moss Couture 1 Scheduled for July 8th, the event was forced to reschedule to the 10th due to a torrential lightning storm, which apparently turned into an epic dance party as guests waited to see if the show would go on. The collection, when finally revealed, included a dress shaped like a jar of peanut butter, a floor-length cape made out of hair rollers, and many other oddities – check out the scene from the rainy show day here.

Jean-Raymond became the first African American designer to be asked by the French federation Chambre Syndicale de la Couture to show a collection during Paris Couture Week. In the notes for the show he spoke about Madame Walker’s legacy, “Her wealth was more than money. … Black prosperity begins in the mind, in the spirit and in each other. She knew that no dollar amount could ever satisfy the price tag of freedom — that green sheets of paper & copper coins could never mend souls, heal hearts or undo the evil we’ve endured.”

In 2018 New Voices Foundation acquired Villa Levaro to turn it into a think tank for black female entrepreneurs, which you can learn all about here. The Madam C.J. Walker brand was relaunched in 2016 under the name MCJW Beauty Culture and can be purchased at Sephora. A delightful, but at times historically inaccurate rendition of her story plays out in Netflix’s series Self-Made, starring Tiffany Haddish and Octavia Spencer. For some more historical salon history reading, check out A Brief History of Salons.