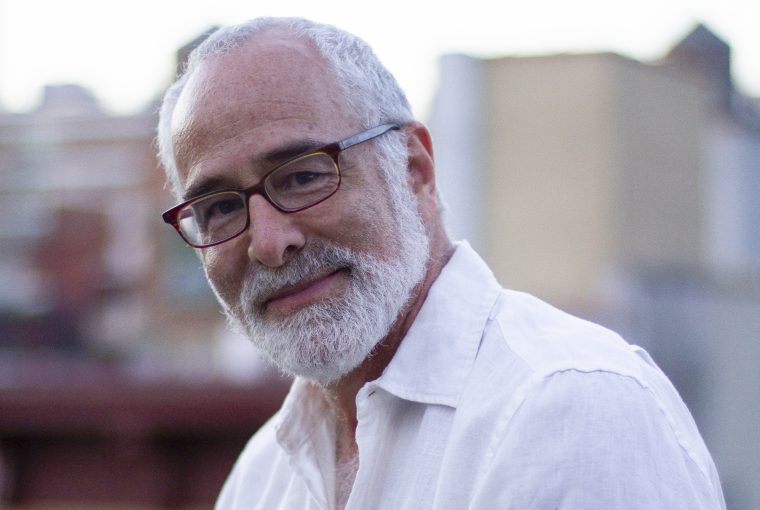

From a tussle with invertebrates to a weed-adverse pastry chef, a legendary New York restauranteur remembers his wildest salons

It started with a Passover seder. In 1994, Peter Hoffman hosted a small gathering at Savoy, his popular SoHo restaurant, when food historian Ray Sokolov stood up and gave a short talk on the influence of Sefardic Jews on Spanish food.

Hoffman was known as a farm-to-table pioneer who put fresh, seasonal ingredients on the menu long before it was trendy, and he had hosted some wine-themed events in the past. But what he really wanted was to do was expand public knowledge of how food, history, and culture intersect. When his sister leaned over and whispered that he should host dinners with speakers like Sokolov, he immediately agreed.

Soon Hoffman had put together a dinner series on the origins of food. The salon took off, evolving to be about much more than food and spanning more than 20 years. Hoffman, whose book, What’s Good? A Memoir in 14 Ingredients, comes out this summer, recounts memories from his days as a salon host.

- How did your salon get off the ground?

The author Michael Pollan, who was then an editor at Harper’s magazine, was a regular customer at Savoy. I got to be friendly with Michael and he came on board. We started off the dinner series doing apples and then heirloom vegetables, which led to discussion of GMOs.

Anybody could come, all they had to do was pay. As opposed to just doing a special menu that lots of restaurants do, this was a salon: everyone sat at communal tables. Serendipity worked in my favor and lots of friendships developed as a result. So the restaurant was not just a private/public eating experience, it became a community event. Once I realized that I leaned harder into it. I thought, ‘This is extraordinary, what can we do with it?’

- How did the salons evolve from being mainly food-focused?

We were doing an evening on wild game and I’d purchased hare shot in Scotland. One table pulled me over to pleasantly complain that they’d gotten the buckshot in their hare. And it turned out to be Galway Kinnell, the poet. I don’t remember whose idea it was to do an autumn poetry-themed dinner, but he ran with it.

In 1995 we’d expanded the restaurant to a second floor lounge that almost felt like a speakeasy. Over the weekend my wife, Susan, and I went on a hike and picked all these wonderful leaves that we scattered down the tables. Guinea hens were on the spit turning in front of the fireplace. It felt like we were no longer in Manhattan.

On the nights we were all dining together with the fire burning and someone reading poetry, you’d think, ‘I’ve been transported.’ With the help of a glass or three of wine people would float off into the night. It was wonderful. I’d taken a step beyond food specific themes, to more conceptual ideas. We did the poetry of New York and the poetry of food. It freed me to think more conceptually.

- Did you have a philosophy guiding the dinners?

I was teaching myself about how the food system works in this country and the world. What is the backstory of where our food comes from? Whether it was exposing the truth about some of the bad things, or celebrating ways in which people were building powerful, positive businesses—those were driving values.

I started to be interested in dishes that are best made in bulk. The idea was to share a platter together. It raises the level of intimacy, and therefore connectedness. So, our world is getting larger and smaller at the same time. Larger because we’re thinking about ideas outside our normal realm together, but also smaller because we’re at the table in a very intimate way.

- What distinguishes a salon from a dinner party?

That there’s a diverse community at the table—not just a group of friends, not even the host knows everybody. It should have a key figure that’s bringing attention to a topic or to themselves, which is going to drive the conversation. So even though it’s a diverse group of people, over the course of the evening they end up all talking on the same topic and thinking about something together.

For me there’s something very sensuous in all of it. It’s not going to a dry lecture, it’s about the pleasures of the table and the pleasures of life.

- Which was your favorite salon?

One was a dinner with Stephen Jay Gould, the evolutionary paleontologist. It was an all-invertebrate dinner. It’s easy to say, I’m gonna do the food and wines of Tuscany and crack an Italian cookbook. But an all-invertebrate dinner—what does that look like? I thought, I’m gonna serve as many bivalve species as I can get my hands on. Plus cuttlefish. Honey from bees. Ginkgo nuts were growing in the early evolutionary period, so let’s do that too. The night included a crisis in the kitchen when the sea urchin shells began to crack from the heat and water seeped into the ginkgo nut custard they were holding.

We presented a biodiverse experience without being exploitive of the species. We were honoring them, not just because of their exoticism, but because of what they represent in the tree of life.

- Have you had any near or full-blown hosting disasters?

So Michael Pollan’s book, The Botany of Desire, is broken into four chapters. Apples: sweetness. Beauty: tulips. Control: potatoes. Intoxication: marijauana. We were doing a dinner based on that. The week before, I was having a conversation with the pastry chef about what desert was going to be. As a joke, I’d written on the invite, ‘Sorry, no hash brownies.’

The pastry chef said you should get marijauana from the girls upstairs. We shared a common stairway with two women who smoked a lot of pot and you’d often smell it in the hallway. I said, ‘That’s a great idea, we’ll make hash brownies and regular brownies and people can decide.’ I was half serious but I wasn’t really going to serve it.

Then, Sunday morning I got a call from the sous chef, who said, ‘The pastry chef just turned in her keys and said she can’t work for someone willing to break the law.’ I spent the day calling her, but she had packed up and left New York. I was the straw that broke the camel’s back of life in the big city.

The dinner was completely sold out. My wife is a pastry chef, but at that point we had two little kids and she hadn’t worked in a restaurant for years. I asked her and she said no. But I begged and so she came in and made apple strudel—for the sweetness chapter—for 50 people, two nights in a row. For intoxication, we served brownies. I wish they were hash brownies but they weren’t.

- How can you tell if the evening has been a success?

When I can’t get people’s attention—no matter how hard I’m banging on a glass after the appetizer—because they’re so engaged with talking to each other. That was always a sign for me: what was the decibel level in the dining room and how difficult was it to get people’s attention?

- Is there a salon theme you’re still hoping to try out?

My son is an opera singer and there’s an event that Franz Schubert started, the Schubertiad: an evening of song and food and wine. It often turned into an orgy of sorts. I’m not proposing that. But I’d like to do something musical, whether it was with my son or other musicians. The idea of mixing food and sound would be exciting to work on.

- Who’s your dream salon guest, living or dead?

One of the food writers and natural world writers I like a lot is John McPhee. He wrote a book about oranges a long time ago, and I’d written to him about doing a themed dinner. He responded with a handwritten note saying he was too busy and “by the way March is too late to do a citrus dinner.”

Another was the food critic Jim Harrison who was a real gourmand in both his deep appreciation for—and probably living with a fair amount of excess in—eating and drinking. I even agreed to let him smoke in the dining room, but he still chose not to do it.

- What’s your best advice for an aspiring host?

The importance of keeping the food logistics simple. People are there for community and for conversation, and the exact specifics and intricacy of the food doesn’t matter. It needs to be good first and complex second or third. Keep it simple.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.