The adventurous streak that would later make Natalie Clifford Barney one of Paris’ most legendary salon hosts was sparked by a chance encounter with Oscar Wilde in 1882.

Barney was five years old and being chased by a group of young boys at a beachfront hotel in New York when she ran past Oscar Wilde, who snatched her onto his lap and told her a mesmerizing story. She later described their meeting as her “first adventure.” The mother and daughter were spending the summer at Long Beach Hotel, the same seaside retreat where Wilde was giving a lecture. They spent the next day with him on the beach, changing their lives forever.

Wilde encouraged Barney’s mother to pursue her old dream of becoming an artist. (She would become a renowned painter whose works were acquired by the Smithsonian.) And Barney would spend the rest of her life seeking more adventures far from the high-society she was born into in Dayton, Ohio.

Barney knew she was gay as a preteen and was outspoken about her sexuality at an early age. “My queerness is not a vice, is not deliberate, and harms no one,” she once wrote. In 1900, she published Some Portrait-Sonnets of Women, a collection of love poems to women, making one of the few women to write openly about lesbian love since her idol, the Greek poet Sappho.

The book’s illustrations were provided by her mother, who was apparently unaware that the models she was sketching were romantically entangled with her daughter. Soon after, Barney’s father died and left her a large sum of money. She used part of it to open her salon.

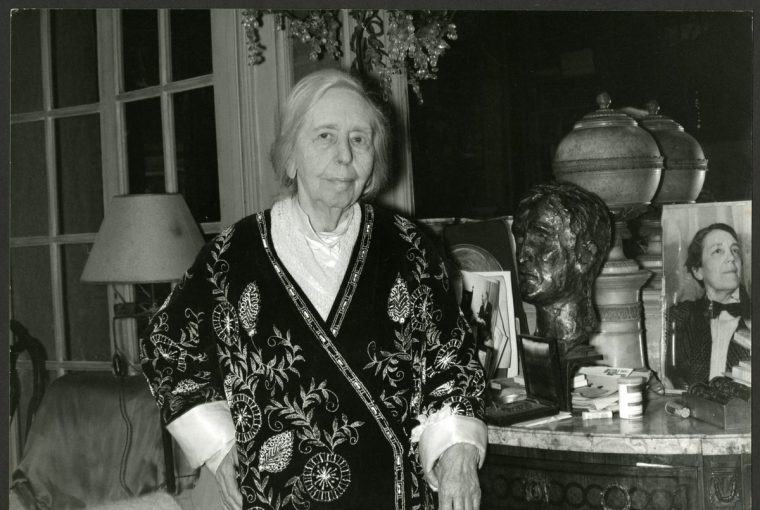

For more than 60 years, Barney ran one of the most decadent, open-minded salons on Paris’ Left Bank. Soon after she moved into 20 Rue Jacob, in 1909, she launched what she called her “Fridays,” a weekly salon that attracted the most famous names in art, dance, literature, and music. Sometimes there would be performances, other times readings. The setting was a large windowed salon room and a small, four-pillared Grecian-style temple, called the “Temple d’Amitie,” or temple of friendship. (This video interview from 1966 gives a peek into her home and reflections on her most famous guests.)

Barney floated among guests like James Joyce, Colette, and Isadora Duncan in a long white dress. Tea was served, with triangular sandwiches, chocolate cake, and an ever-flowing supply of punch and whiskey. Her friends called her “The Amazon,” a nickname the poet Remy de Gourmont gave after as she rode a horse astride, not sidesaddle, on her morning rides in the Bois de Boulogne park. “If I had one ambition it was to make my life itself into a poem,” she said.

Many queer artists were drawn to the openness and safety of Paris, and among the most famous gathering spaces was Barney’s salon. Her mom and sister, Laura, had moved to Paris, too, and the family provided constant fodder for the gossip mill. Once, in 1910, Laura erected a nude statue of Natalie in their front lawn, and the police were called to cover it with a tarp.

Nothing could stop the “Fridays.” Though many salon gathering spaces converted into hospitals to aid the effort during World War I, Natalie was a staunch pacifist and continued to host as usual.

When, in 1927, the Academie Francaise, refused to allow women in, Natalie’s launched the “Women’s Academy” in the temple, inducting her most esteemed salon guests and providing a counterpoint to Europe’s exclusionary institutions.

Around the same time, Barney invited Gertrude Stein to a salon in her honor, where Stein read her work and the composer Virgin Thomson set her librettos to music. After that, Stein could often be spotted at the salon dressed in tweed and boots. “She seemed a game warden scrutinizing the birds,” recalled one guest. Stein herself had a famously open living room, where artists of all walks would drop in for advice and commiseration, but she and Barney were never in competition for guests.

One neighbor, who lived in an apartment overlooking Barney’s pavilion, later wrote her memories of the gatherings: “The hazardous Fridays as Paul Valéry called them. Why do I always remember them as though there’d been a light rain? Natalie’s house looked like an aquarium, with underwater light. There was never any sunlight in the salon because the light was filtered through the big trees in the garden. There were chairs all around the salon, as in a schoolroom, with people sitting all around the walls.”

Barney wrote 14 books, including volumes of poems and essays. Three of those books contained just the witty one-liners she was famous for, including: “Youth is not a question of years: one is young or old from birth,” “There are more evil ears than bad mouths,” and “Eternity—waste of time.”

Along with writing, she was famed for her prolific romances, refusal to be monogamous, and dalliances that often made their way into published novels and poetry of the era. Coincidentally, more than 40 years after meeting Oscar Widle, Barney began a relationship with his niece, Dolly Wilde, which lasted until Dolly’s death 14 years later.

The salon was put on hold only during World War II, when Barney was in Italy. After the war, she returned to Paris and reopened with a new cast of regulars, including Truman Capote. But in the late 1960s, new owners purchased her home and began a gut renovation despite protestations from Barney and history loving Parisians. Barney died in a hotel in 1972, 95 years old and far from her origins in Dayton, Ohio.

Her life had spanned from first-wave feminism, which began in the mid-1800s, to the women’s liberation movement of the 1960s. On her tombstone, an epitaph she wrote acknowledged a legacy much larger than one mere life: “Je suis cet être légendaire où je revis”—“I am this legendary being in which I will live again.”