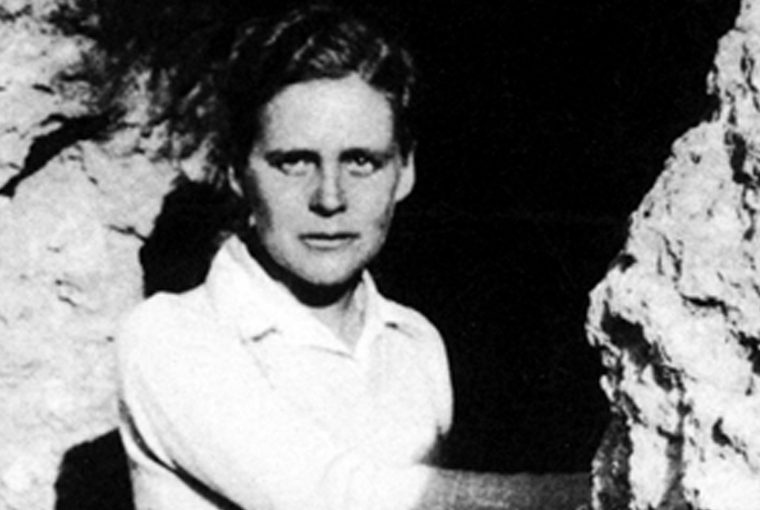

Meet the woman who ran “atomic salons” for the Manhattan Project.

Edith Warner was operating a small tea room along the rail line in Los Alamos, New Mexico, when she met Robert Oppenheimer. Oppenheimer was then a theoretical physicist at the University of California at Berkeley, but soon he’d taken on a new role: to build a weapon that could win World War II. As director of the bomb laboratory of the Manhattan Project, he was in charge of a top-secret effort to create the first plutonium-based atomic explosive.

Warner’s house was a modest single-story brown stucco structure that sat next to the Otowi Suspension Bridge. Before the outbreak of the war, her job was to oversee the “Chili Line,” a railtrack that had once tried to stretch from Denver to the Mexico border. When the train was discontinued in 1941, Warner began to serve tourists and travelers in her tea room.

But by then, the U.S. military had locked up the area for security reasons. Warner lived right across from “Project Y,” code named to disguise its use as an atomic weapons lab led by Oppenheimer. The scientists who moved there would later invent the Little Boy bomb that was dropped on Hiroshima and the Fat Man, dropped on Nagasaki, in a site locals referred to as “the hill.”

They had chosen the land of Los Alamos Ranch School, a former outdoor program for boys just 35-miles outside Santa Fe, and converted it to hold the scientists, staff, and families of the Manhattan Project. Los Alamos was wiped off maps, and addresses were replaced with a single P.O. box number (eventually, 5,000 people would be registered to that box).

Warner considered moving but Oppenheimer, who had first stopped into her tea room on a trip in 1937 had grown infatuated with her chocolate cake and lively company. He asked her to stay, and begin hosting dinner parties where his isolated and overworked scientists could let loose and socialize. In 1943, she reopened to unofficially serve the Manhattan Project.

In a house decorated with Native American artifacts, and paintings, a long table fit up to 10 guests, who tucked into Native dishes like posole corn-soup, and chocolate cake every Friday night. The food was fresh: Warner grew her own vegetables, and her chickens laid the eggs that went into the famous cake.

With an armful of bracelets and concho belt cinching her waist. Warner bustled about, rarely pausing. Frances Quintana, who grew up nearby, helped her with the tasks, and once told an interviewer that Warner never sat down with her guests. “She was always on the go,” Quintana said.

Before long, the parties had months-long waiting lists. They were soon deemed crucial to keeping up the morale and attitudes of those working on the nuclear bomb. Warner and her hosting partner, Atilano Montoya, a quiet Native Elder, became the gateway between the two communities: confused locals and secretive scientists.

Part of Warner’s role may have been as a way to keep the project quiet. Scientists and their spouses would sometimes head into Santa Fe to unwind, and the government feared they might reveal what they were working on. In fact, at least two physicists were dispatched to spread false rumors of electric rockets. They weren’t wrong to be worried. German physicist Klaus Fuchs, secretly working for the Soviets, would arrange meetings with his handler in Santa Fe, eventually handing over enough information that the Soviet Union was able to fast-track its own atomic bomb.

Warner’s warmth and wisdom was appreciated by the Manhattan Project scientists, and she formed life-long bonds. One chemist even helped her rebuild her home when a flood washed it away. “There are many things for which I would express my gratitude,” Warner wrote in a letter to Oppenheimer in 1945. “Your trust in me not only solved an economic problem but greatly broadened my horizon. Your hours here mean much to me, and I appreciate, perhaps more than most outsiders, what you have given of yourself in these Los Alamos years.”

The Manhattan Project shut down In 1947. Four years later Warner died of cancer, but not before widely distributing her chocolate cake recipe to the departing members of the project. She was buried in the back of her house, which still stands today.