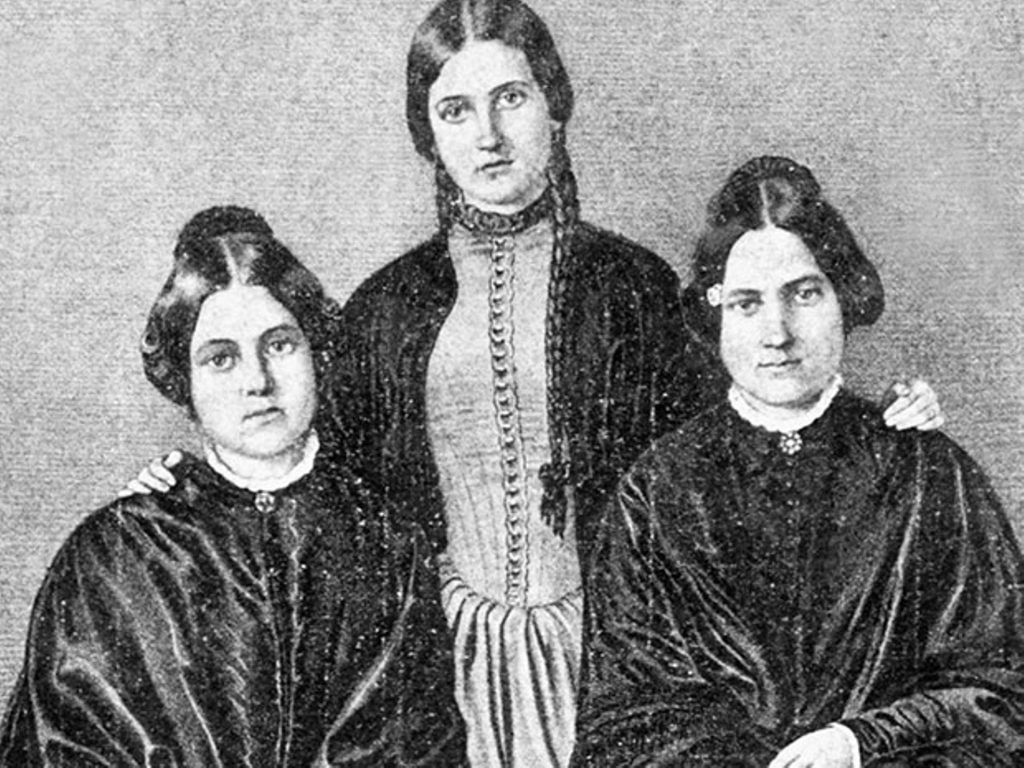

In the late 1840s, a small wooden house in Hydesville, New York, drew an endless crowd of curious onlookers hoping to see two young sisters communicate with spirits. The home of Margaretta and Kate Fox was about to become the center of a movement that would enthrall the country. For the next eight decades, spiritualism turned dining room tables across America into hubs of reverence and debate for believers and skeptics alike.

The Fox sisters were soon drawing crowds of hundreds to their seances, including notable figures like New York Tribune editor Horace Greeley and abolitionist Sojourner Truth. Before long, women across the country were claiming that they too could communicate with the world beyond. The Fox sisters conveyed their messages in mysterious rapping noises, but in other mediums it took the form of written messages, possession, and even gelatinous substances that emerged from their bodies.

The craft quickly became associated with women. Though mediums were sometimes men, the sensitivity and intuition considered innate to women were seen as crucial traits for connecting with the dead. Spirits, it was believed, could only be channeled through a passive personality.

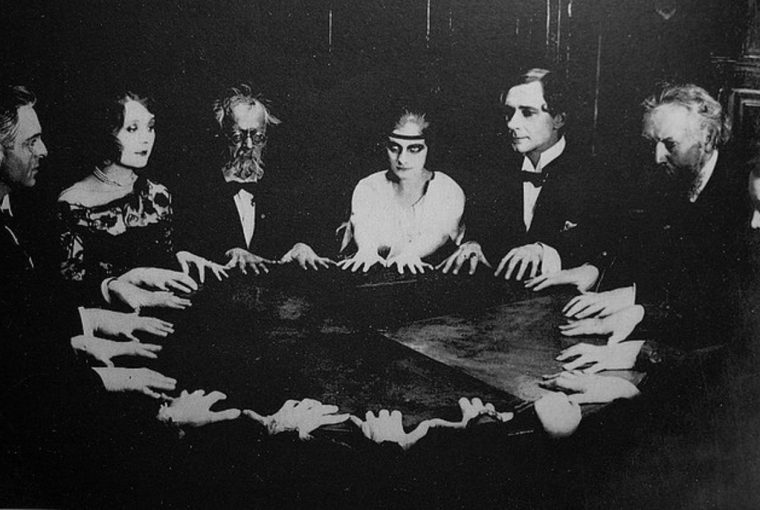

Somewhat ironically, then, the seance table became a rare place where women commanded the attention of men. They took on personas that would have otherwise scandalized the crowd, but were accepted under the guise of channeling deceased spirits. They could swear, flirt, and yell in anger.

Not since the emergence of the salon in 15th century Europe (read more in A Brief History of Salons) had women been allowed a platform to host their peers and lead discussions on important matters (learn even more in our Women’s Role in Salons article). As the lady of the house, serving as host was a traditional role, but with certain tweaks it could be harnessed into something with more gravitas. Now, spiritualism provided that same opportunity.

“Power was in the drawing room,” writes magician Careena Fenton, in a blog post about women and the seance. “Sitters at the seance were in their thrall, money and gifts changed hands in return for an evening’s entertainment. The ladies of the seance room achieved autonomy and infamy.”

Though the table itself wasn’t a place for lively discussion—darkness and silence being key components—what happened around it roused the public and imbued reverence to its hosts. The most famous mediums could even influence the highest echelons of society.

In 1862, Mary Todd Lincoln lost her 11-year-old son Willie to typhoid. Soon after she began hosting seances in the White House. Around the time that Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation, a medium named Cora Maynard was presiding over groups in the Red Room, and possibly even Lincoln himself.

“Those present at her seances, when her spirits had counseled on important affairs of state, ‘had lost sight of the timid girl in the majesty of the utterance, the strength and force of the language, and the importance of that which was conveyed, and seemed to realize that some masculine spirit force was giving speech to almost divine commands,’” writes historian R. Laurence Moore, citing Maynard’s own recollections.

Mediumship, he adds, was “one of the few career opportunities open to women in the nineteenth century.”

The same thing was happening on the stages of lecture circuits, when mediums under trance amazed crowds of men by delivering screeds on subjects they were assumed to have no knowledge of—from the latest scientific discoveries to foreign affairs. For the first time, women were given a voice in male domains. Some seance hosts, claimed to be guided by famous dead artists, made artwork and exhibited it widely.

Mediums were able to travel as professionals and would be gone from home for stretches of time. After the Civil War, spiritualist conventions became strongholds of support for feminist leaders fighting to liberate women from domestic duties.

Periods of great loss preceded each spike of spiritualism fervor. Desperate parents and spouses of the young men lost on remote battlefields fueled an industry of those claiming to be able to contact them. In the late 1860s, after the Civil War, the seance table had risen in popularity, and it would again later, after the death toll from World War I.

In the Victorian era, mediums had often been dismissed as deviants by broader society, but by the second wave of spiritualism, in the 1920s, they increasingly garnered respect. The revival of spiritualism was backed by prominent figures of the day, particularly Sherlock Holmes author Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and British physicist Oliver Lodge.

Researchers, too, took a renewed interest, intent on proving or disproving the existence of another realm. Paranormal communication was considered a legitimate field of study, and panels of the most esteemed medical and scientific minds were put to the test. Harry Houdini, then the world’s most famous magician and escape artist, was among the most successful and dogged debunkers of psychics and mediums.

Culminating in Congressional testimony in 1926 during hearing about a proposed bill outlawing so-called fortune tellers and clairvoyants, Houdini spoke vehemently against those who claimed to have communication with the non-physical world. “There are millions of dollars stolen by clairvoyants and mediums every year, and I can prove it. Conan Doyle is the biggest dupe outside of Sir Oliver Lodge.”

Before long, those who allowed themselves to be studied were unveiled as frauds. “The moment that mediums and séances were moved from the darkened room of home and hearth and into the laboratory of the researcher, women lost all authority in the world of the supernatural,” writes Leila McNeill in the magazine Lady Science.

The seance table was no longer a place where women could stake their claim as respectable leaders. But the world had changed, and soon history would catch up such that they wouldn’t have to hide behind spirits to gather a group of friends for a discussion of the day’s pressing topics.